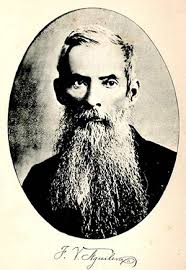

Francisco Vicente Aguilera and Tamayo. (June 23, 1821 Bayamo- February 22, 1877 United States). Major general, lawyer and Cuban politician who fought in the war of 68. He had a great fortune that he sacrificed for the freedom of the Homeland; he was also the owner of mills, farms, abundant cattle and large estates, but a Cuban endowed with a noble heart and excellent patriotic sentiments.

He treated the most humble people as equals and with respect and consideration, for which he was much loved. He always rejected the numerous public positions and jobs offered to him by the island's rulers and colonial authorities. Even that of "perpetual alderman of the Illustrious City Hall of Bayamo." He joined the insurgent forces, in which he reached the rank of Major General and first held the position of Secretary of War, and then that of Vice President of the Republic in Arms.

In 1867 he founded the Revolutionary Committee of Bayamo. His revolutionary thought was radicalized. The date of the uprising was discussed, subordinating it to the existence of military supplies with which to confront the Spanish Army. Aguilera was of the opinion that he should be postponed so that he could stockpile weapons. And it is at this moment that he agrees to move to the United States and return before December 24, the maximum date accepted by the conspirators to pronounce themselves, with enough war material to start the Revolution. The events were precipitated and on October 10, 1868, in the Ingenio La Demajagua, Céspedes starred in the uprising.

Already in the war, Aguilera held important political-military responsibilities. Carlos Manuel de Céspedes decided to send him to the United States to unify the emigrants and achieve the sending of expeditions with logistics with which to supply the troops of the Liberation Army.

In this determination of Céspedes several reasons must have weighed, among them that Aguilera had been a supporter of this idea before the beginning of the Revolution, due to the knowledge he possessed in managing funds, since he had created a millionaire fortune, as well as for his thought and way of acting, which had turned him into a paradigm of unitary thought. The different political factions, civil and military, saw him as a man of integrity, ethics and revolutionary.

Aguilera left to fulfill this mission despite the contrary opinions of his friends who insisted that it was a political ability of the President to remove him from the Cuban political scene, remove him as a possible rival, and aspiring to the presidency. Despite these criteria, he was convinced that at that time the Homeland was where he needed it, to solve the existing problems.

The vice president

At a time when divisions, bids and intrigues were common, many could not understand another of Aguilera's decisions: to recognize Carlos Manuel de Céspedes as the leader of the Revolution.

And it is that "Pancho" Aguilera had actually been the founder and head of the first Revolutionary Junta of the East, created in August 1867. A year later, the revolutionary conspirators of this region of Cuba recognized him as the maximum leader of the movement that was gestated.

That is why, after the Demajagua uprising, some gossipers went with ill-intentioned gossips and told him the possibility of taking over the pro-independence leadership.

But it is evident that the landowner was more interested in the redemption of the nation than in personal hierarchy, for this reason, when the date of the uprising was suddenly brought forward and when Céspedes assumed the leadership of the contest, he placed himself at the service of the Initiator, from his estate in Cabaniguán, in Las Tunas. In this regard, the researcher Raúl Rodríguez La O wrote:

«With a troop made up of his foremen, employees and slaves, to whom he had granted their freedom, he marched towards Bayamo, with the aim of reinforcing the Cubans in the attack on that city, on October 18»

Proceeding with that humility earned him so that in that same month Céspedes named him Division General. Some time later, due to his merits, he was awarded the rank of Major General and then the positions of Lieutenant General of the East, Secretary of War and Vice President of the Republic in Arms.

Precisely with this high position he left for the United States in 1871, a country in which, among other missions, he had to settle the irreconcilable differences between two factions of Cuban émigrés who said they supported the Revolution.

After the absurd deposition of Céspedes in 1873, "Pancho" Aguilera would have assumed the presidency of the Republic, but when they informed him of that possibility, he indicated that he would not return to the country until he brought a large arms expedition, something for which he fought with his soul.

The affirmation is not born as a compliment. The facts prove it: in the first half of 1875 he left for Cuba as leader of the Charles Miller steamship expedition, but countless navigational problems made the ship return to New York, the city where he had settled and from where he wrote time later, according to the historian Onoria Céspedes Argote:

“These Yankees are the epitome of selfishness. This is today the concept and the hopes that inspire me».

As if this failure were not enough, in 1876 he tried to enlist in an expedition on the steamer Anna, but another setback made him give up on his plans.

Latin Americanist

The period lived in emigration contributed to radicalize his vision of the United States. Many Cubans dreamed of the help of this country to achieve independence. As a result of the relationships he established with North American politicians and being the victim of unfulfilled, evasive promises, direct obstacles that made expeditions fail and did not allow the necessary collections, he came to the conclusion that the Government of that nation would never support the Cubans to obtain independence and sentenced:

"They will help Cuba when Cuba has helped itself. To expect more than that is wishful thinking."

There, in addition, he dealt with men of deep Latin Americanist thought such as the Puerto Rican Eugenio María de Hostos, with whom he shared a deep friendship, which allowed him to also be the founder of Cuban Latin Americanist thought, by proposing the need to create an Antillean Confederation to confront the expansionist policy of the United States.

Little was the money that Aguilera was able to raise in the first months of his stay in New York. That is why he decided, in June 1872, to start a tour of Europe. They had promised him that the Cuban capitalists who had emigrated to France would finance him a great expedition.

The reality was different, and he began to suffer slights, subterfuges, the money did not flow, the discussions dragged on, and the bourgeoisie, fearful that their properties would be seized, did not contribute, or wanted to do so without their names being known and therefore the amounts they delivered were ridiculous. These limitations convinced him that he could not obtain the necessary resources in Paris, but he still insisted. He became a missionary for the independence of Cuba.

The European tour defined Aguilera's thinking regarding the Cuban bourgeoisie that had important capital to protect in Cuba. Finally, when he left Paris, in March 1873, as a result of an imperious call made to him from New York upon learning that Céspedes had dismissed him as General Agent abroad, he was fully convinced that he would never return because this sector of the Cuban bourgeoisie would not finance the independence of Cuba.

Stay in Europe

The stay in Europe made it possible for him to establish a rupture that perhaps would have been impossible to conceive at another time, because perhaps he thought that all Cuban owners had the same decision as him in sacrificing their fortune and well-being for the independence of the Homeland.

In his last European days, Aguilera began to show an attitude of managing funds with bankers of different nationalities, who could contribute to the Cuban cause for the economic benefits they would obtain. He definitely distanced himself from the bourgeoisie.

His return to New York meant continuing to work on sending a large expedition to Cuba. But now the situation had changed. He was no longer the General Agent, but an émigré, with the only difference of being the initiator of the revolution and the prestige he possessed for his honesty and disinterest in Cuba's independence. In these circumstances he developed his work, without joining the internal struggles that bled the emigration. And it is from this moment that the profile that we have of him today was shaped. The difficulties he had to go through, the misery in which he lived and died, the hardships of his family left those who knew him stupefied.

The pilgrimage through the United States put him in contact with the Cuban bourgeoisie that had confronted the Spanish metropolis. Here, as in Paris, he was able to verify that he would not obtain the necessary resources. He began a tour of North American cities in order to find a steamer that would take him to Cuba, as well as to raise money. He visited Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Key West. In the latter, an important concentration of Cuban emigrants began to develop, who contributed a considerable amount of money, about seven thousand pesos, between the months of February and April 1874. This detachment made a deep impression on him.

Despite this demonstration, his thought continued to consider that the sums for the financing of the expeditions should be contributed by the Cuban émigrés who possessed the greatest capital. For this reason, he continued to be linked to sectors of the Cuban bourgeoisie in the west of the island, as well as to landowners, many of whom entered into compromises with the Spanish authorities. These ruled out a radical Cuban independence thought. He did not perceive the differences that existed between this sector and the one that had started the independence struggle.

Last years

Aguilera suffered so much laziness that finally, unable to put together a large expedition and lacking resources, he decided to return to Cuba.

On April 22, 1876 he made his last attempt. He arrived in the Bahamas, where he intended to board the Ship Anna, and not finding it, he proceeded to Nassau. On June 12 he sailed for Haiti. The trip was impossible. He arrived in New York on August 15, 1876. He was already seriously ill from the cancer of the larynx that afflicted him, but still he insisted on returning to the Homeland, even if it was on a boat.

On February 22, 1877, Francisco Vicente Aguilera died in New York, while working for the unit of Cuban emigration surrounded by his wife and children, without having been able to fulfill his greatest desire: to free his homeland; nor his dream of returning to Cuba with a strong expedition.

The aspirations of Francisco Vicente Aguilera were more ambitious than those of his ancestors and he focused on founding a political thought that contemplated the idea of achieving Cuba's independence from Spanish colonialism by taking up arms. The aggrandizement that would bring his family would not be in the order of what his father dreamed of, that is, in obtaining a noble title, holding political positions in the government structure of the town or province, or in the militia, but by converting the Aguilera lineage into one of the founders of the Cuban nation.

The millionaire who died for the country

He was tremendously rich; he had so much money that he could spend the rest of his days spending whatever he wanted. And he owned so many extensions of land that he could leave his first haciendas as a child and arrive as an adult on the last ones. To some it may seem like too much hyperbole. However, when it is emphasized that he had more than two million scudi in the year 1868, the mountain of wealth he possessed can be understood. And despite so much gold and wealth, Francisco Antonio Vicente Aguilera, that fine-mannered Bayames little studied by past and current generations, went to war renouncing everything material to try to achieve the spirituality of the nation.

He finally died poor and almost frozen by the New York cold, with holes in his shoes and frustration in his soul for not being able to return.

You can write about Aguilera without shaking your hand: "He gave everything for the country," a phrase that has sometimes worn itself out from so much repetition, but which in his case is doubly convincing. With him, as with others, one owes a debt: to study his example more, not only on days of "closed birthdays" or scientific conferences on the hero.

Riches

Not in vain has it been pointed out that Francisco Vicente, nicknamed "Pancho" Aguilera, was one of the richest men in the East in the days of conspiracies prior to the outbreak of independence.

It has often been written that he owned more than three million shields and about 10,000 caballerias, in addition to hundreds of slaves as well as some trade between Bayamo and Manzanillo: several houses, thousands of head of cattle, hundreds of horses of different types, a bakery, confectionery and other properties scattered throughout the Cauto Valley, to the south of Las Tunas.

However, Ludín Fonseca, historian of the city of Bayamo and author of the book Francisco Vicente Aguilera. Modernizing project in the Cauto valley, points out on the first figures that the patriot actually owned about 2,700,000 pesos and 4,136.50 caballerias between farms, pastures, sugar mills, a coffee plantation, haciendas and other extensions of land.

Regarding the number of their slaves, the Bayamese researcher Idelmis Mari points out that, although "they amounted to hundreds, they did not occupy a preponderant place in the amount of properties, because in the mills, a branch where they were mostly employed, 191 in Santa Gertrudis, 87 in Jucaibama and 14 in Santa Isabel».

But beyond the discussions about his wealth, the first thing is to recognize his detachment and patriotic behavior, which amazes many in these modern times.

Let us bear in mind that Aguilera had 11 children —ten of them with Ana Kindelán Griñán, from Santiago de Cuba, also wealthy and whom he had married in 1848—, and that the liberating war against Spain implied leaving comforts, going to the jungle and exposing theirs to their own mountain or into exile.

A hero of the stature of Manuel Sanguily, on that example of Francisco Vicente Aguilera, stated:

«I do not know that there is a life superior to his, nor any man who has deposited in the foundations of his country and in his nation a greater sum of moral energy, more substance of his own, more privations of his adored family nor more toils or torments of the soul ».

While José Martí, with his burning pen, described him in the newspaper Patria, on April 16, 1892, nothing more and nothing less than "the heroic millionaire, the irreproachable gentleman, the father of the republic."

These affirmations of someone like the Master are not gratuitous. Aguilera, perhaps in the best-known passage of his life and that immortalized him as a revolutionary, was able to say when asked about the decision to burn the city of Bayamo, where some of his domestic properties were located:

"I have nothing as long as I have no country."

Mausoleum

Aguilera's remains have rested in Bayamo since 1910. However, the story of the transfer of his mortal remains to the country and the subsequent burials is so rich that they are well worth another journalistic report.

They were even stolen from the San Juan cemetery so that they would not be moved to the Santa Ifigenia necropolis of Santiago. This chapter and others involved thousands of Bayamese, defenders of his patrician heritage and of the birthplace of this man, who was a law graduate and held various public positions before launching himself into the redemptive jungle.

The truth is that, in 1958, the mausoleum was inaugurated in homage to the patriot, on whose base his remains rest. Near this stand the figures of other illustrious Bayamese, which is why the monumental complex is called the Altarpiece of the Heroes.

From that place, Aguilera looks at his people not as a cold rock, but as a living and fighting man. From his heart the words that he sent to his compatriot José María Izaguirre seem to tremble:

"The day we have a homeland we will not touch the ruins of our old Bayamo, we will preserve them as they are, so that our descendants can see what their grandparents were capable of."